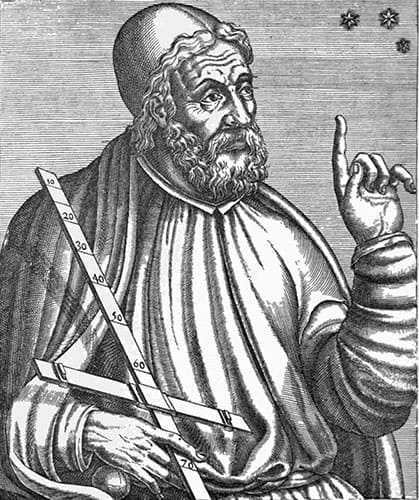

Claudius Ptolemy, an ancient astronomer, was a renowned scientist who authored multiple scientific treatises that had a significant impact on both Western and Eastern sciences. His works continue to be referenced by contemporary geographers.

Ptolemy, the Astronomer

Claudius Ptolemy, also known as Claúdios Ptolemaîos, was a renowned Greek astronomer and astrologer who dedicated a significant portion of his life in Alexandria, a city located in the Roman province of Egypt. While not much information is available regarding his personal life, it is crucial to highlight his invaluable contributions in the form of writings, research, and groundbreaking discoveries.

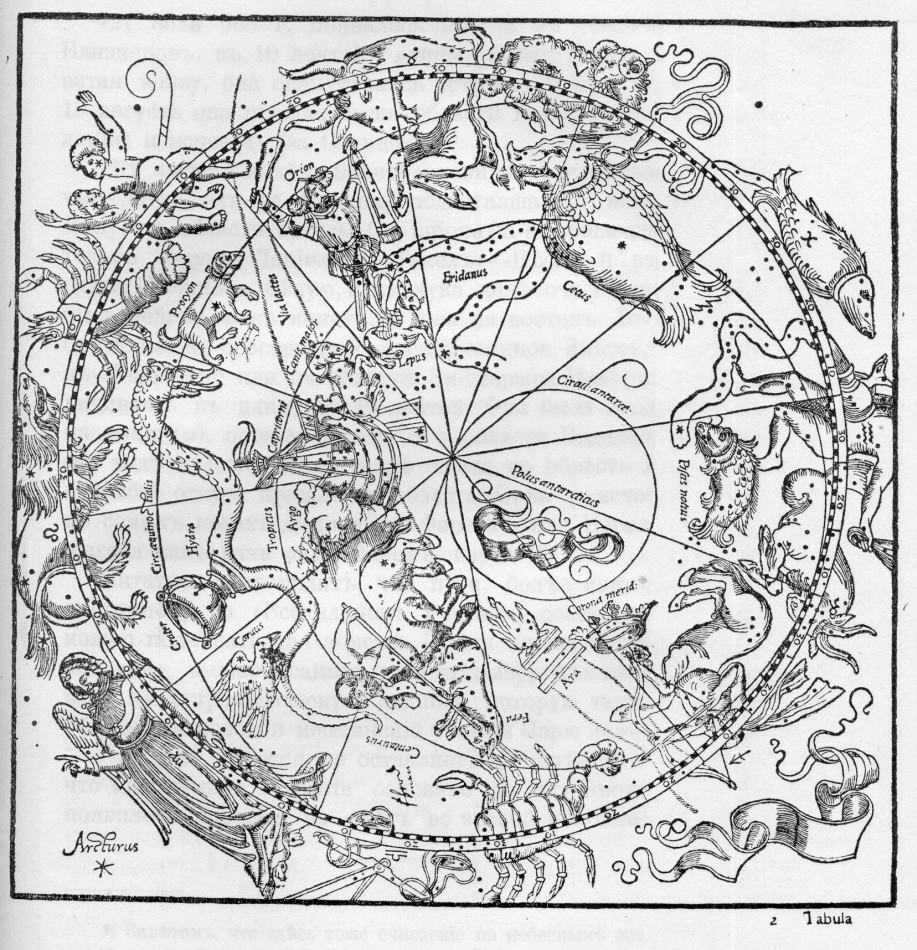

Ptolemy’s masterpiece, the Almagesta, is an unquestionably remarkable work. This treatise on astronomy spans across 13 volumes and combines the knowledge and observations of the Babylonians, Byzantines, and Greeks, encompassing nearly nine centuries of astronomical advancements. Notably, the Babylonians contributed significantly to the collection of observations, providing information on the positions of stars and dates of eclipses. They also played a crucial role in the calculation of various astronomical phenomena. Ptolemy, in his work, even incorporated the observations and calculations of notable Greek astronomers like Eudoxus of Cnidus and Hipparchus, utilizing their findings to determine the movements of specific celestial bodies.

It is worth noting that Ptolemy’s model will endure with varying degrees of success over the ages and across different civilizations until advancements in observational tools are achieved. Without a doubt, the heliocentric theory proposed by Nicolaus Copernicus, further refined by Johannes Kepler, and staunchly supported by Galileo, would ultimately bring an end to an age-old model that the Church would not relinquish until 1750!

Ptolemy: A Renaissance Figure in the Field of Geography

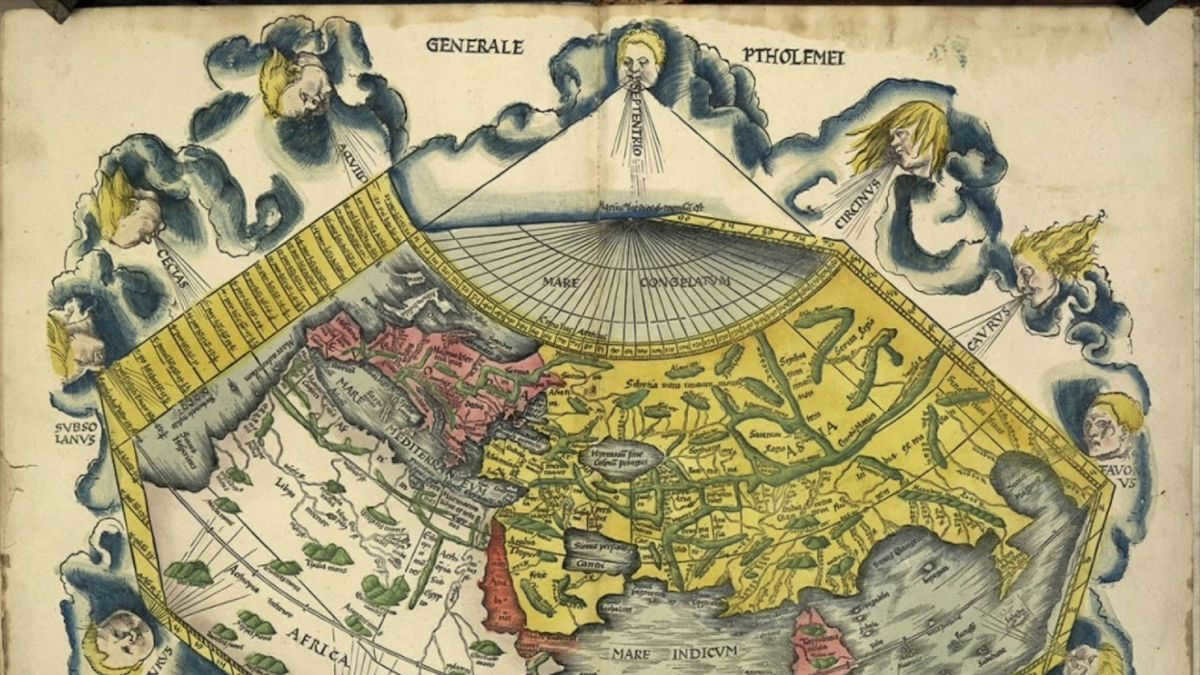

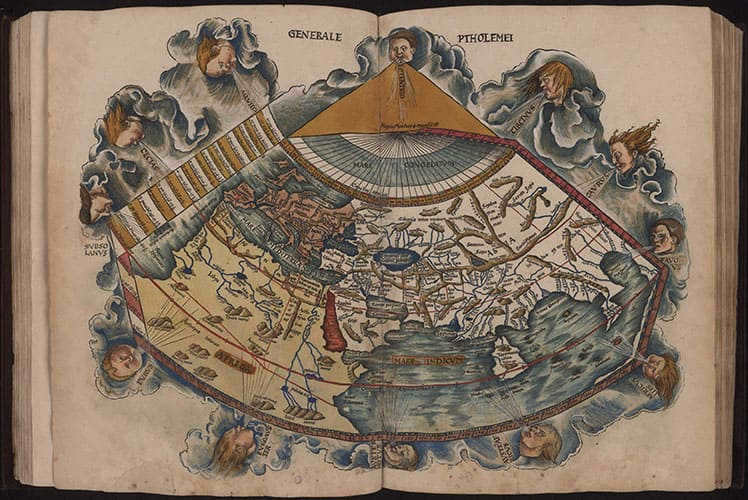

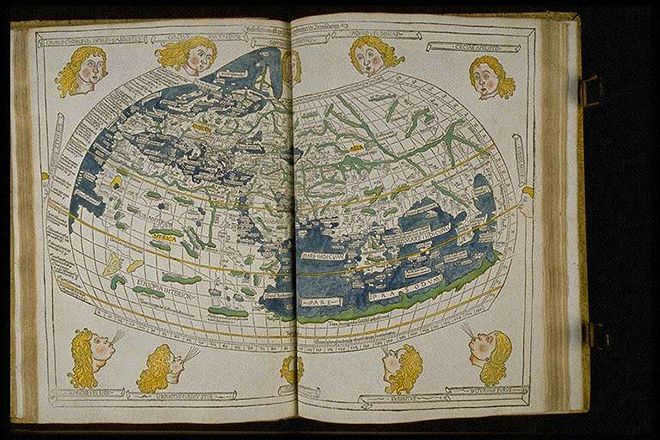

Ptolemy, an influential figure in the history of geography, is often referred to as one of the fathers of the discipline. His second treatise, titled Geography, has had a profound impact on both Western and Eastern scientific thought. This extensive compilation of geographical knowledge was created during the Roman Empire, specifically during the reign of Emperor Hadrian (117-138). Spanning the entire known world, this work serves as a comprehensive introduction to cartography, consisting of eight volumes. Even in modern times, students of geography continue to study and appreciate Ptolemy’s groundbreaking contributions.

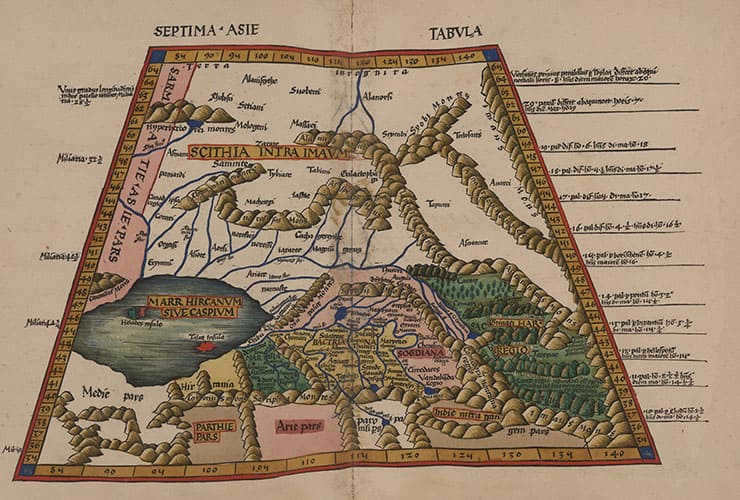

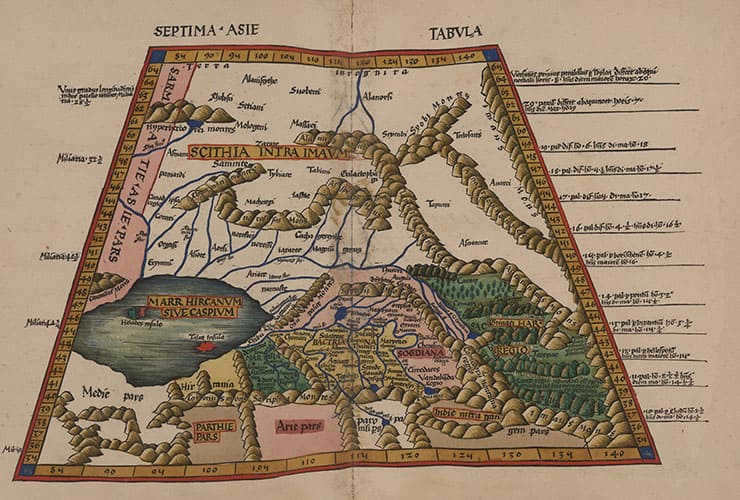

The initial book defines geography and presents the approach and information utilized to create a map of the recognized world. In volumes 2 to 7, Ptolemy catalogs a minimum of 8,000 locations in Europe, Asia, and Africa with coordinates, offering topographical lists. These, from the west to the east, encompass Ireland, Great Britain, Germany, Italy, Greece, North Africa, Asia Minor, Persia, and ultimately India, using their present-day names. In the ultimate volume, Ptolemy introduces a division of the recognized world into 26 regional maps, particularly, twelve for Europe, four for Africa (referred to as Libya), and twelve for Asia.

The geographer Ptolemy made a different estimation of the Earth’s circumference, putting it at 33,345 kilometers. This estimation is farther from Eratosthenes’ estimation of 39,375 km and the actual distance to the equator, which is 40,075 km.

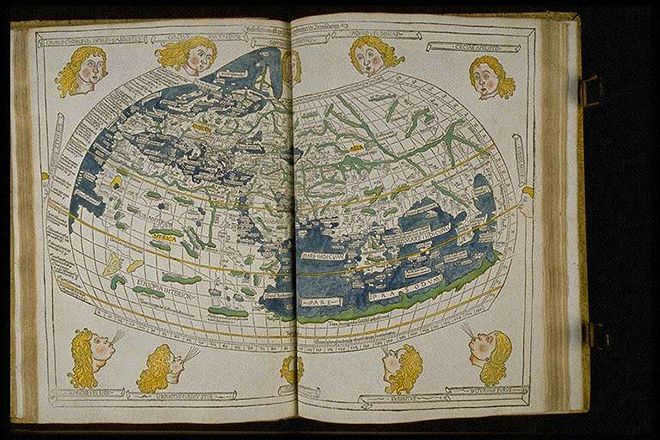

Ptolemy, building upon Eratosthenes’ maps, improved the methods of map projection based on Euclid’s geometry. He developed two methods for projecting a sphere onto a flat surface, both of which had a significant influence. The first method represents meridians using segments, while the second, more complex method represents arcs (see below). In terms of regional maps, the cylindrical projection developed by Marinus of Tyre was already in use and not new.

Claudius Ptolemy wrote various additional texts on astrology, musicology, mathematics, and optics. One of his most renowned astrological works is the Tetrabiblos. This book primarily focuses on horoscopic astrology and uses a chart based on a table that determines the positions of the seven planets known during that era, including the Sun.

His book on the theory and principles of music, Harmonica, is a comprehensive guide that explores the mathematical aspects of music. Ptolemy examines musical intervals in relation to mathematical proportions and presents his own unique divisions of the tetrachord and octave, which he derived using the monochord. It is worth mentioning that Ptolemy was not only a musicologist but also a renowned mathematician, with one theorem even being named after him. This theorem states that in a convex quadrilateral inscribed in a circle, the product of the diagonals is equal to the sum of the products of the opposite sides.

Another significant work by Ptolemy is Optics, where he delves into the properties of light such as reflection, refraction, and colors, as well as presents his theory of vision. However, it is important to note that the Latin translation of this text by Eugene of Sicily, completed around 1150, is itself an incomplete and imperfect translation from its original Arabic source.

Russia, Muscovy, Scythia, and Sarmatia are depicted on Ptolemy’s geographic maps. Which territories are represented on Ptolemy’s map?

Last updated: 02.05.2023

Who was Claudius Ptolemy?

Claudius Ptolemy, born in 100 AD and died in 170 AD, was a renowned astronomer, mathematician, and geographer who resided and conducted his research in Alexandria, Egypt during the Roman Empire. He is most famous for his comprehensive work titled “Great Mathematical Construction on Astronomy in Thirteen Books” or commonly known as “Almagest”. In this masterpiece, Ptolemy compiled and synthesized the astronomical knowledge available at that time from both Greek and Eastern sources. His contributions include detailed observations and calculations on the movements of celestial bodies, the description of constellations, and the development of astronomical tables.

Claudius Ptolemy’s second most significant achievement was his “Guide to Geography,” an eight-book work that served as a comprehensive summary of all the ancient knowledge about world geography. This renowned guide reportedly included 27 detailed maps of various countries and regions, such as 10 regional maps of Europe, 4 maps of Africa, and 12 maps of Asia. Unfortunately, the original copies of these maps have not survived to the present day. However, the text portion of the treatise, which contains precise geographical coordinates for over 8000 locations, was discovered in the late 13th and early 14th centuries. Based on this surviving text, the lost maps were recreated and reproduced.

It is worth mentioning that ancient writers did not mention Ptolemy, so during his time he did not have the necessary authority and recognition. This has led some scholars to question his actual existence and view the maps as a recent forgery. Nevertheless – these maps do exist and are remarkably precise for their era, indicating that they are built upon genuine knowledge – regardless of the identity of their creator.

When we refer to an object being shown “on Ptolemy’s map” nowadays, it’s important to note that we are actually referring to these “reconstructed maps”. The true appearance of Ptolemy’s maps remains unknown. However, if the discovered treatise with coordinates is genuine, then it is likely that the maps have been recreated quite accurately. This allows us to glimpse into the distant past and observe how Ptolemy’s contemporaries perceived the world, a century after the time of Jesus Christ. It also sheds light on what existed in the lands that are now modern-day Russia during those centuries.

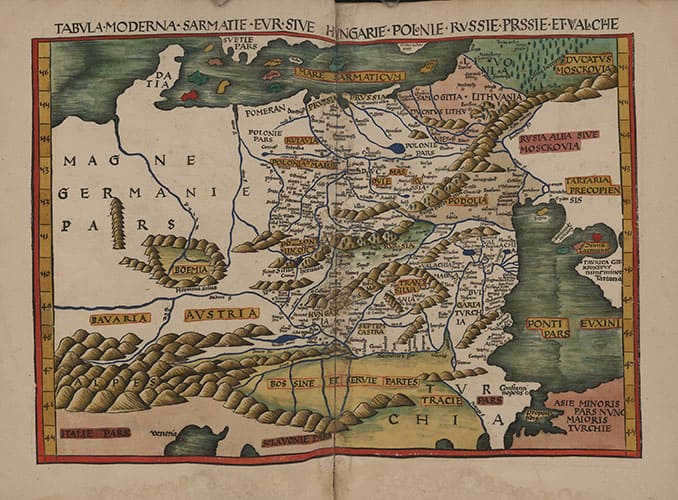

*There are multiple variations of restored maps created by different authors. Typically, each subsequent map was based on the previous one, resulting in them being virtually identical. In terms of content, the restored Ptolemaic maps of the Ancient World are the earliest, followed by a series of maps in a similar style labeled “tabula nova” and “tabula moderna” – these are presumably “modern” maps added during the restoration of the old maps, around the beginning of the 14th century.

Below the text, we will be using the 1513 version of Ringman Mattais, which can be found in the online library of the University of Virginia.

What was Ptolemy’s depiction of Russia on maps?

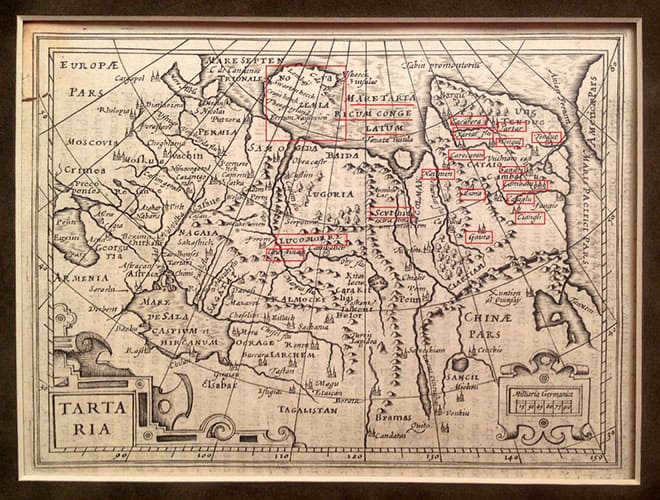

During Ptolemy’s time, the concept of Russia did not exist. Instead, he referred to the region as Sarmatia and Scythia. However, in later maps from the 14th century, these names were replaced with Moskovia and Tartaria.

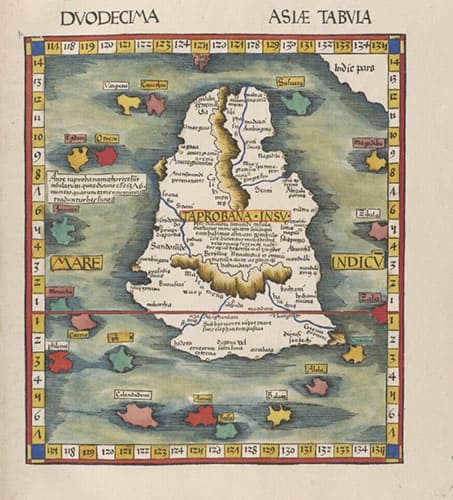

However, prior to examining the maps, it must be mentioned about an unusual “blank space,” which curiously “aligned” with our territories. Ptolemy meticulously documented all of Europe, Africa (incidentally, Ptolemaic maps of the central region of Africa remained the sole cartographic depictions of these areas until the 19th century), India, and even the ancient island known as Taprobana. However, Russia was not as well-documented – he essentially skirted along the far western border, providing more or less detailed descriptions of what we now recognize as the European part of Russia, but what lies beyond the Ural Mountains remains unclear. Isn’t it peculiar that Ptolemy possessed a greater knowledge of distant India than of the Ural Mountains?

Taprobana (Sri Lanka) on Ptolemy's map.

However, it is important to note that these maps are not original, but rather restored versions. This raises the question – has everything been fully restored? Without the maps, we are left with no answers. They have become a “non-historic land,” conforming to the general paradigm of world history. But what if there is more to the story? What if Ptolemy had knowledge of numerous large cities in eastern Scythia (Siberia and the Far East)? This would certainly be inconvenient. It is possible that such information was censored when the maps were restored in the 14th century. Interestingly, modern copies of these maps, available in the public domain, do not include page numbers. This raises further doubts about the accuracy and completeness of the digitized versions.

Now, let’s examine the content that is accessible to everyone.

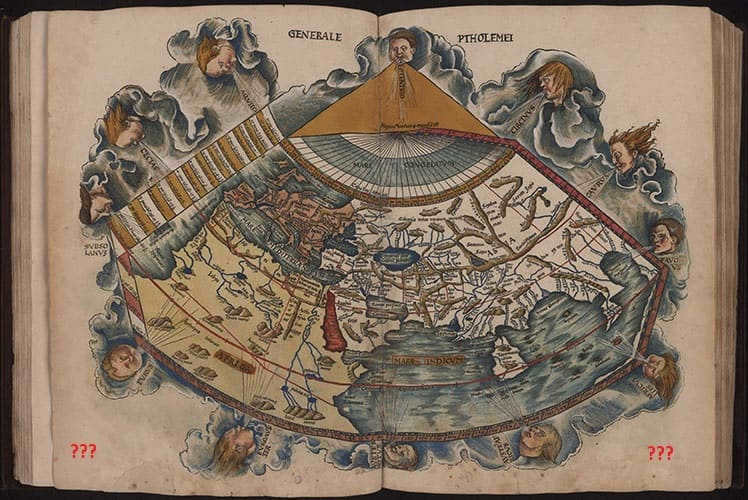

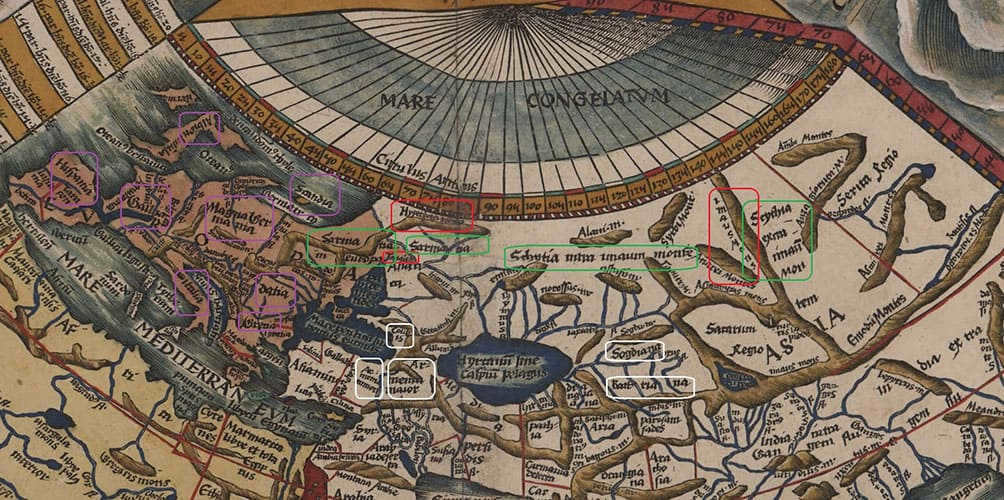

Let’s begin by examining the world map and its significant coordinates. For instance, Europe (highlighted on the left) and Asia (highlighted on the right) are not divided by the Ural Mountains, as is commonly accepted, but rather by the Tanais River – specifically, the Don River.

Additionally, the map (in purple) showcases various countries in Europe, including Spain, Gaul (which is now known as France), Germany Magna, Italy, Dacia, Greece, Albion (which refers to Britain), and Scandia. It’s worth noting that Scandia is depicted as an island, albeit a very small one when compared to Albion. This suggests that Ptolemy may have only been aware of the southern tip of Scandinavia. Or perhaps, we are once again confronted with areas of uncertainty and ambiguity?

Europe also encompasses a portion of Sarmatia, which roughly corresponds to Eastern Europe and central Russia. The remaining portion of Sarmatia falls within Asia. These regions are identified as follows: Sarmatia in Europe and Sarmatia (presumably Asian) – indicated in green.

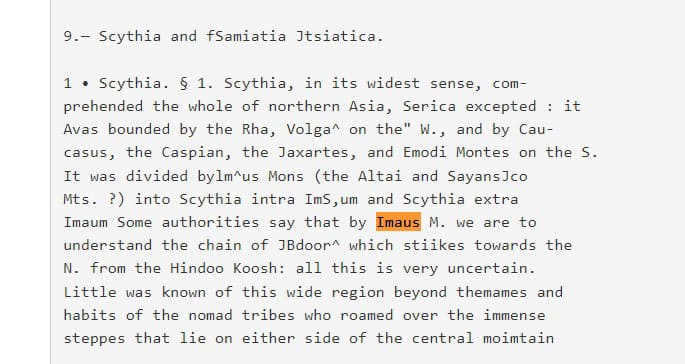

To the east of Sarmatia lies Scythia, which is also divided into two parts: Scythia intra **** montes and Scythia extra **** montes – or Inner and Outer Scythia, also marked in green. The division between them is clearly defined by the mountains – montes – which are explicitly mentioned in their names. Looking at the map, these mountains are referred to as Imausmens (red). We attempt to locate this term using search engines and come across an English-language textbook on ancient geography by the author, which contains an important paragraph on the borders of Scythia:

According to the description, it can be inferred that Altai and Sayans are considered by some modern researchers to be the Imaus mountains mentioned on ancient maps, while others believe it to be the Hindu Kush range.

Lastly, to provide some context, we can mention (highlighted in white) a few other notable locations: Colchis (located on the modern Black Sea coast, specifically in Krasnodar Krai, Sochi, and Abkhazia), Armenia Major and Minor, Bactriana, and Sogdiana.

European Sarmatia

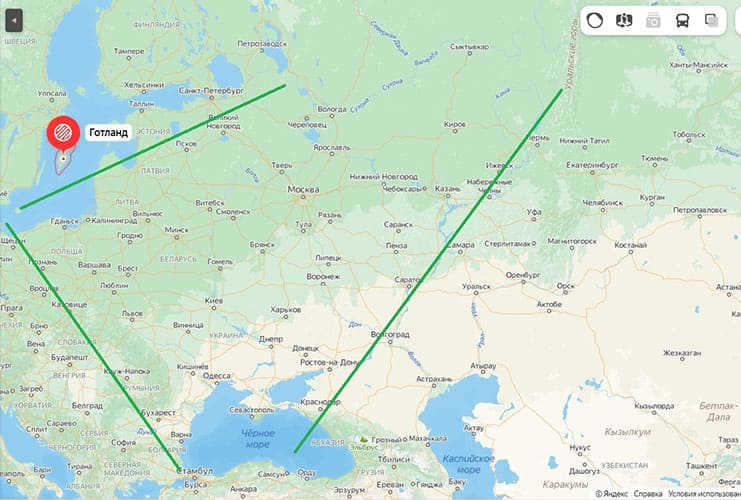

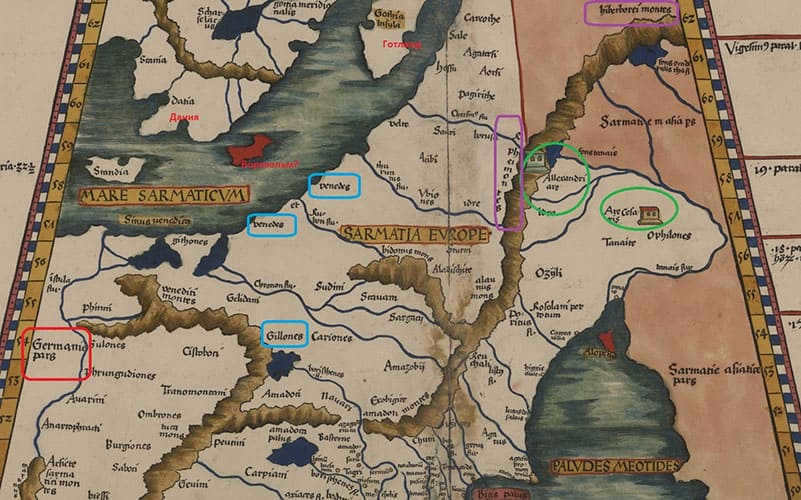

Now let’s proceed to more intricate maps. Let’s begin with European Sarmatia. According to Ptolemy’s interpretation, European Sarmatia encompasses all the territories stretching from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea. To the west, it shares a border with Germany, while to the east, the boundary extends along the Tanais River and/or the Ripean Mountains (which transform into the Hyperborean Mountains to the north).

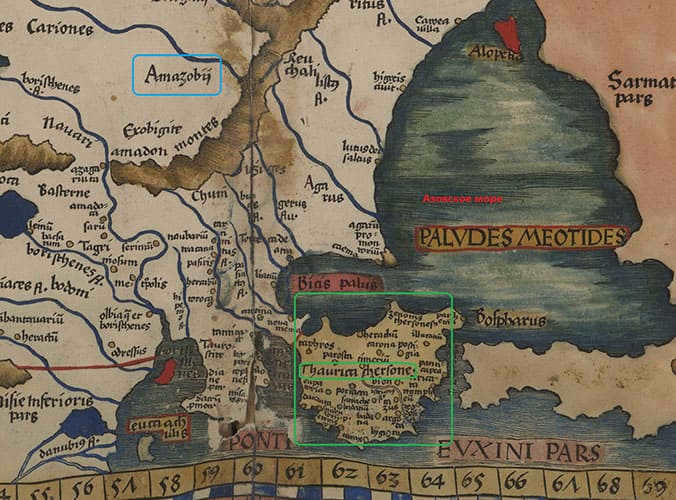

The approximate correspondence of the region European Sarmatia according to Ptolemy can be seen on the modern map in green.

This map does not display cities, only the rivers are labeled (in Latin) and it appears that the names of tribes are also indicated. Among them, we can recognize the Venedi (highlighted in blue frames), which is often mentioned as a synonym for Scythians by many ancient authors. Another tribe mentioned is Gellons – Herodotus wrote about them as one of the tribes of Scythia.

The inclusion of the Baltic Sea and Kadetrinne Strait as part of the Sarmatian territory on the map is intriguing. This suggests that the Sarmatians were skilled seafarers and had a legitimate claim to rule over these waters. Otherwise, a different name would have been assigned to this area.

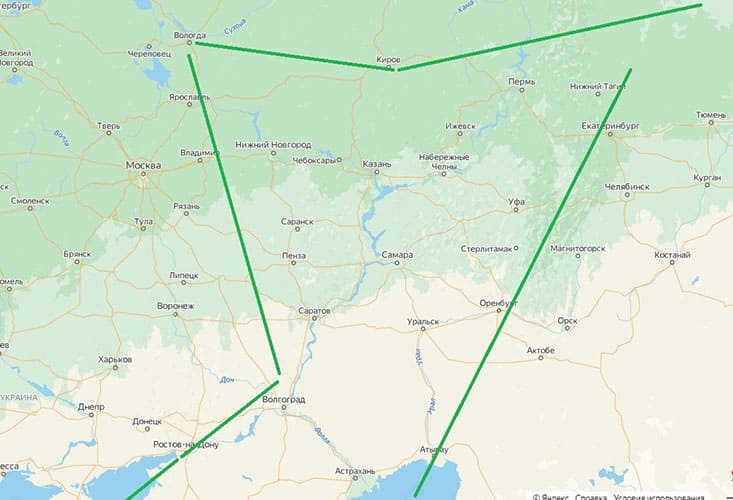

Regarding the placement of the structures, Ptolemy’s map suggests that Are Ces(f)aris is situated in the vicinity of the Don River’s significant bend, which comes close to the Volga River. On the other hand, Allexandri Are is believed to be located in the Southern Urals. Nevertheless, it is evident that there is an error in the map, as the Don River’s bend is actually much further west from the Ural ridge, contrary to Ptolemy’s depiction.

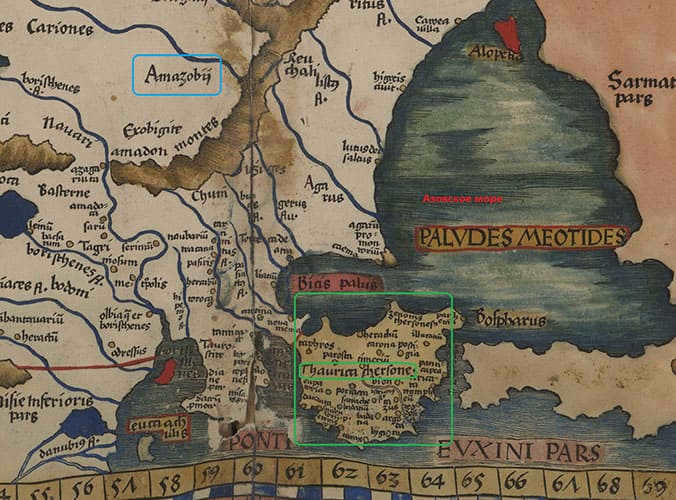

The region of Crimea, referred to as “Taurica Chersonese” on Ptolemy’s maps, is of particular interest. It has the highest concentration of cities compared to all the other regions of European Sarmatia, and possibly even other regions. The mention of the “Amazons” (highlighted in blue) is also noteworthy, as according to other ancient sources, these female warriors inhabited the northern shores of the Sea of Azov and/or the area where the Volga is closest to the Don.

Asian Sarmatia

According to Ptolemy, the heart of Asian Sarmatia is the Volga River, known as the Ra (Rha) river. This connection is unquestionable and is documented in numerous ancient sources. The western boundary runs along the Don River (Tanais), while the northern part of Asian Sarmatia is covered by the Hyperborean Mountains (it is now clear that they run from west to east, not from north to south) – and if we accept the hypothesis of S. Zharnikova and equate them with the Northern Uvals, the border of the designated Hyperborean Mountains will approximately follow the line.

The region of Asian Sarmatia as described by Ptolemy is approximately depicted by the green area on a contemporary map.

Sarmatia fully encompasses the Caucasus Mountains and the entire Black Sea coast in the southern region. It is distinguished from the more eastern Scythia by a red line, which is not aligned with any specific rivers or mountains. This indicates that there was no clear border between the two regions. The Scythians and Sarmatians are considered to be the same people with similar appearances and customs, and the terms “Scythians” and “Sarmatians” are used interchangeably by different authors. The only difference between them is their administrative divisions into different kingdoms. For example, in Ptolemy’s writings, there is a reference to the “kingdom of Mithridates” labeled as “Mitridat regio”.

Incidentally, the “History of Russian from the most ancient times” (1770) by Prince Mikhail Scherbatov provides a comprehensive account of the Scythian kings individually, including their names and significant actions. In this publication, the Scythian history takes precedence over the Russian history, with the latter being a direct continuation of the former. This viewpoint was widely accepted by historians, both Russian and foreign, only a century ago. To delve deeper into this topic, we recommend reading a thorough article that analyzes the sources supporting the notion that the Scythians and Slavs are essentially synonymous.

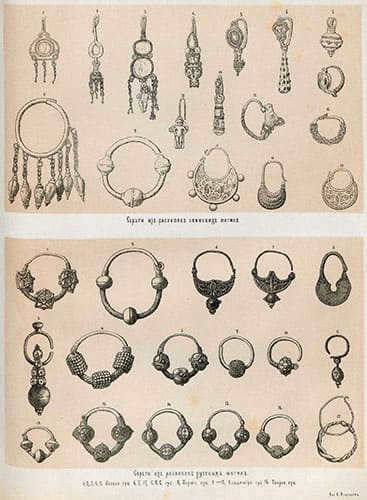

Shown above are earrings discovered in excavated Scythian burial sites, while the earrings below were unearthed in excavated Russian graves.

However, let us revisit Ptolemy’s map. It is worth noting the significant population inhabiting the Krasnodar territory and the Black Sea coast! While the map of European Sarmatia did not mark a single city, here there are barely enough space to fit them all, both along the coast and in the upper reaches of the local rivers. The official historical accounts do mention the Bosporan kingdom, which existed in Crimea and the eastern shore of the Sea of Azov from the 5th to the 6th century. However, the cities along the Black Sea coast are only mentioned as isolated coastal towns in connection to this kingdom. In Ptolemy’s map, the Black Sea coast – from present-day Anapa to Abkhazia – appears as a distinct center of the region, comparable to Crimea (as shown on the map of European Sarmatia – see above).

Map of the Bosporan Kingdom

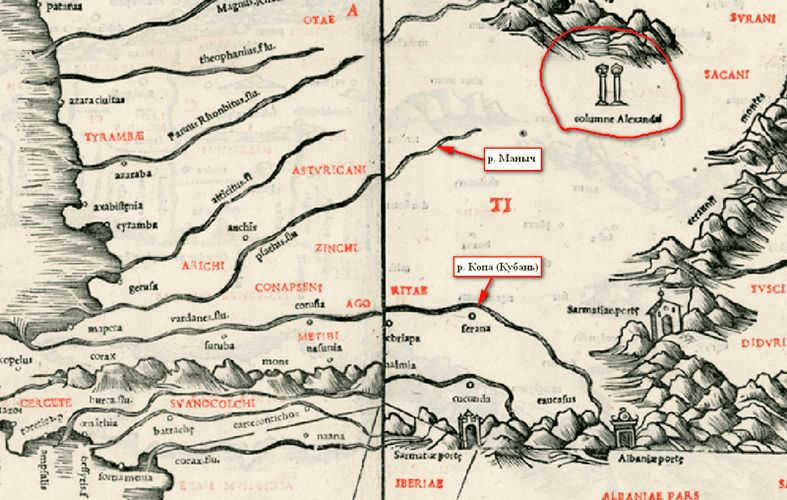

It is intriguing that even though this page is already dedicated to Asian Sarmatia, the author decided to include here the aforementioned landmarks – Allexandri Are and Are Ces(f)aris, which are associated with European Sarmatia – due to their significant importance. Additionally, a few new landmarks have been added: the Columns of Alexander (highlighted in green) and several gates in the Caucasus Mountains (depicted on the map above within green frames).

Regarding the columns – indeed, numerous ancient authors have recorded that Alexander positioned columns along the path of his army as a form of marker. These columns signified “conquered but not conquered” and served as a point of reference for subsequent soldiers in his army, who recognized that they were advancing through a relatively friendly territory where Alexander had already left his mark.

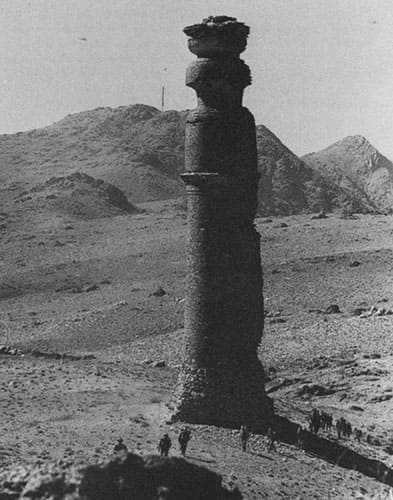

Legends of such columns exist throughout Central Asia, leaving no room for doubt regarding their existence. Unfortunately, none of these columns have survived in their entirety to the present day. One of the most recent examples may have been Alexander’s Column in Afghanistan, which was destroyed during the recent war but remains captured in photographs.

The Kabul Tower, built by Alexander the Great

The columns named after Alexander in the Volga region are not only mentioned by Ptolemy, but also appear on numerous other maps. After comparing these maps, researchers have even discovered the precise location of these columns… the village of Aleksandrovskoye in the Stavropol Territory.

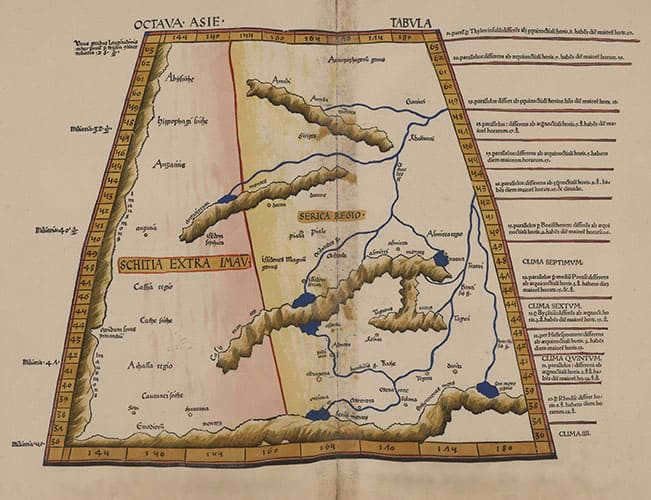

A portion of Bernard Sylvanus’s Tartary map from 1511.

However, that is not the entirety. In close proximity to the aforementioned village, there are indeed ruins of such megalithic structures. Should you desire, there is an abundance of supplementary information and local folklore surrounding them.

The area near the village of Aleksandrovskoye in the Stavropol Territory is captured in this photo taken by Sergey Sidorenko

And what about the enigmatic gateways found in the canyons or on the slopes of the Caucasus Range? Could they be entrances to caves or vaults, or did they hold some significance and serve as barriers, impeding the enemy’s passage?

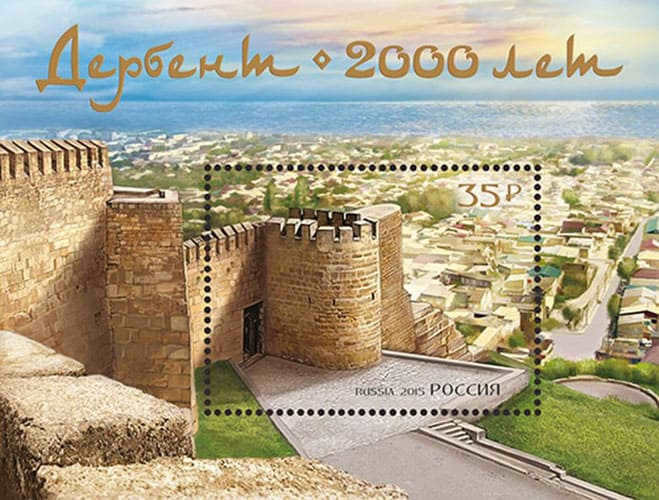

In the publication “A Thousand Roads”, issue number 2, from May 2007, there is a mention of ancient records stating that Alexander’s army engaged in intense warfare with the Scythians on the northern shore of the Caspian Sea. In the area that is now Derbent, there existed a narrow passage through which the Scythians could access the sea. This passage was blocked by Alexander with what he called “iron gates”. Essentially, the gorge was filled with a combination of ore and a special flammable mixture, effectively sealing off the passage forever. This is how the name Derbent, meaning “iron gate”, came about. There are alternative versions of this legend. According to local historical sources in Dagestan, the fortress known as Iron Gates (Derbent) already existed when Alexander the Great arrived in the area (and he did indeed visit these places!). The fortress fell after a fierce battle, but one of the wise and proud local elders impressed Alexander so much with his words that he appointed him as his viceroy.

The gate mentioned in the text can also be found in the Quran (18:83-101), where it is mentioned that Alexander’s gate will crumble into dust before the end of the world.

There is no information available about the other two gates mentioned on Ptolemy’s map. However, there is an intriguing story connecting Alexander with the Caucasus. Ancient authors recount Alexander’s possession of a remarkable golden helmet, believed to have been gifted to him by Apollo himself. The Quran provides a description of this helmet – referring to Alexander as “Iskander Zulkarnain,” meaning “Alexander Two-horned” – suggesting that the helmet carried ancient symbolism associated with the bull, which was significant throughout the region (we will explore this further in a separate discussion).

Mount ZZmeika, Mineralnye Vody.

Inner Scythia

When comparing the maps of Sarmatia to the maps of Scythia, it becomes clear that Ptolemy’s knowledge of the latter was rather limited. Alternatively, it is possible that the cartographers who recreated his maps in the 14th century intentionally depicted Siberia as barren and undeveloped. There are no indications of cities or points of interest.

On this map, we can only see the names of tribes and rivers, but unfortunately, nothing is legible or recognizable. I just want to mention a few things about the tribes – the map is filled with various names, but don’t assume that all of these are completely different peoples. Ancient authors themselves often used the terms Scythians and Sarmatians as a way to generalize and then listed the names of smaller tribes, each of which belonged to the larger community.

In the same “Tale of Sloven and Rus” (read the detailed article), it is mentioned that the Scythians, who left the Black Sea (!) and migrated north with Sloven and Rus, established cities with the same names – Slovensk (the predecessor of Great Novgorod) and Rusa.

“…And henceforth, the Scythian immigrants were referred to as Slovians.”

Moreover, upon their return to the Novgorod territories following the devastating pandemic and subsequent decline:

After a long period of desolation, the Scythian inhabitants heard about and decided to establish a new town in a different location. This new town was built in the area around Volkhov, extending from the old Slovensk downwards. They named it Nov, and the elder prince from the Gostomysl lineage was appointed as its leader. Similarly, Russa was rebuilt in its original location, and many other towns were also revived and scattered across different latitudes of the earth.

Some of the inhabitants settled in the fields and became known as Polans or Poles, while others were called Polochans. There were also those who became known as Polatians, Mazovshans, Zhmutyans, Buzhans along the Bug River, Dregovichi, Krivichi or Smolians, Chud, Merja, Muroma, and many others with various names. As a result, the country began to expand significantly, and the collective name given to this land was derived from the oldest prince of Novgorod, Gostomysl’s son.

Scythia Beyond

The representation of Scythia Beyond is even more abridged compared to that of Scythia Within. Nevertheless, it displays three urban centers, each marked by distinct symbols: two featuring a crimson dot, while the remaining one is denoted by a pale dot. Regrettably, it remains uncertain what the discrepancy between these symbols signifies, as well as which specific cities they represent.

According to Claudius Ptolemy, Outer Scythia shares a border with the region of Serica in the east. Serica is often associated with China, although this connection is not entirely accurate and lacks sufficient evidence due to the absence of recognizable names. It is possible that Outer Scythia actually refers to our Far East, especially considering that medieval mapmakers depicted a high concentration of cities in this area and referred to everything east of the Ural Mountains and up to the Pacific Ocean as Tartary.

Jan Jansson’s map of Tartary, 1640-1650.

Ptolemy: Tabula moderna

Lastly, let’s examine the maps included in the Ptolemaic collection in the modern section (during the “restoration” of old maps based on preserved coordinates – this was around the 14th century).

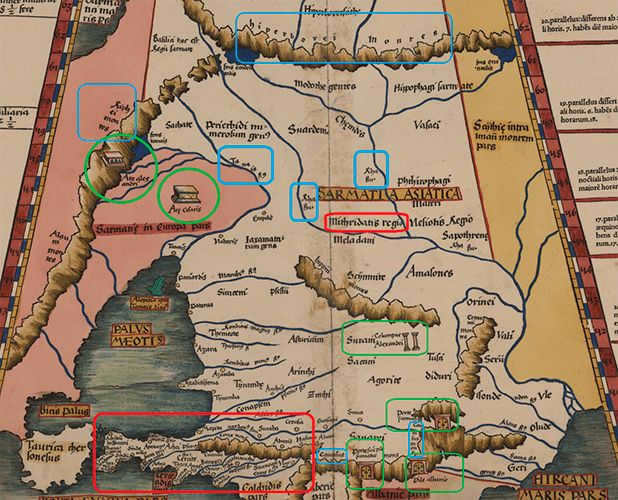

Therefore, European Sarmatia was divided into Pomerania, Prussia, Polonia (both Great and Small), Mazovia, Podolia, Bulgaria, Transylvania, Wallachia, Samogitia, Livonia, and Lithuania. Its easternmost regions were known as White Russia (or Moscovia, as indicated on the Latin map) and the Principality of Moscovia.

It should be noted that the boundary from the west is clearly marked by the river Odra, beyond which lies Germany Magna. This is significant as it marks the end of the historical territories of the Sarmatians and the beginning of lands belonging to other tribes.

The name Russia is also worth noting: in addition to White Russia (also known as Moscovia), it appears twice more on the map (highlighted in red below).

There are a few legible names – Grodno, Polotsk, Riga, Smolensk, and Moscow are recognizable. Moscow is located near the Ripean Mountains, the outline of which remains unchanged compared to ancient maps by Ptolemy. It is interesting to note that even after so many centuries, the exact location of the Ural Mountains (or the Northern Uvals) has not been accurately determined.

Furthermore, there is a particular region known as Cuyavia (located in the top left corner of the map), but Kiev is absent from the map and is situated to the north of Greater and Lesser Polonia.

Additionally, the name Tartary is mentioned twice on the map – one instance being Perekop Tartary (which interestingly enough, is not divided by a border with White Russia, as if it were a single state), and the other being Crimean Tartary (indicated by the green frames).

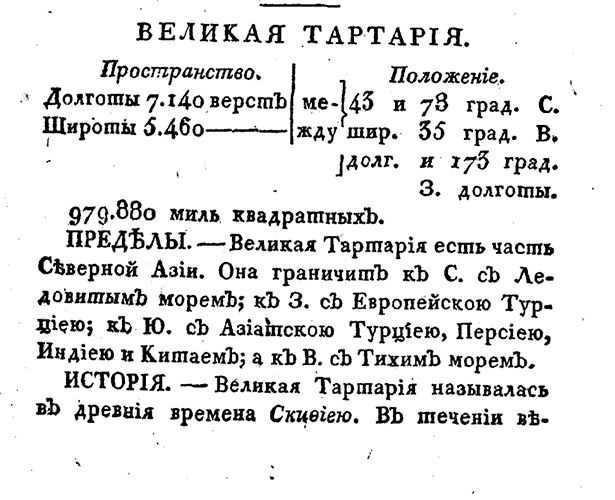

In connection to this, it is worth noting one last detail that is often overlooked but is quite significant. As far back as 1809, William Guthrie stated in his handbook, The Newest General Geography, which describes all the countries of the world, that "Great Tartary was called Scythia in ancient times."

“The Newest General Geography” by William Guthrie, 1809.

There is another significant validation of this fact: on certain maps, the Arctic Ocean is labeled as Scythian, while on others it is called Tartary, and there are even some maps where both names coexist simultaneously.

Mercator’s map of Russia, 1595. Fragment.

Therefore, Tartary is not a fabrication or forgery at all. Nor is Scythia. Both exist exactly where they have always been, since the time of Ptolemy. And both signify the same thing.

Moreover, the people are identical. Scythians. Sarmatians. Slovenes. Russ. Vedes. Ants. Roxolans. Tartars. They are all part of us. Prince Mikhail Scherbatov, who traced Russian history back to the era of the Scythian kings, unquestionably understood what he was writing about.

Meet Claudius Ptolemy, an ancient Greek scientist who made significant contributions to the field of astronomy. Ptolemy was based in Alexandria, Egypt from 127-151, where he developed a groundbreaking scientific theory on the movement of celestial bodies around our planet using the precise discipline of mathematics. During this time, it was commonly believed that the Earth remained stationary, a notion shared by many ancient scholars. Ptolemy’s theories formed the basis of the Ptolemaic system, which encompassed the motion of the Moon, Earth’s only natural satellite, as well as the Sun, our primary source of light and heat.

The Impact of Ptolemy on the Advancement of Sciences

Claudius Ptolemy played a crucial role in the history of scientific development. His scientific writings greatly influenced the fields of astronomy and natural-mathematical sciences. Ptolemy’s exceptional works in ancient natural science have left a lasting impact on the scientific community.

“Almagest.”

Image from the Almagest

Copernicus’s renowned masterpiece, “On Rotations”, served as the cornerstone and stronghold of modern astronomy, building upon the foundation laid by “Almagest”. Claudius devoted considerable attention to astronomical matters and authored numerous scientific works following the publication of “Almagest”.

“Hypotheses of the planets.”

In his work “Planetary Hypotheses,” Claudius introduced a compelling theory about the movement of planets as a unified entity within the confines of the geocentric world system he embraced. “Planetary Hypotheses” may be a concise piece, but it holds immense significance in the history of astronomy’s evolution. Comprised of two books, the work provides a comprehensive account of the astronomical system as a cohesive living organism.

A page taken from the 1484 edition of the Tetrabiblos.

Created the famous work “Handy Tables” containing instructions that continue to be used by scientists, specifically astronomers, up to the present time. This remarkable treatise by Claudius Ptolemy delved into the realms of astronomy and astrology, providing profound insights and contributing to a deeper understanding of the universe. “Handy Tables” stands as a monumental book of its era. Ptolemy’s opus consists of numerous tables meticulously designed to accurately determine the positions of celestial bodies. Unfortunately, a few of Ptolemy’s works have been lost over time, leaving us only with their titles. Ptolemy’s extensive studies in the natural and mathematical sciences firmly establish him as one of history’s most eminent scientists. His works, including the timeless treasure “Almagest,” have garnered global renown and continue to serve as a valuable repository of scientific knowledge. Ptolemy’s broad perspective, exceptional ability to synthesize and systematize information, and his skillful presentation of scientific principles are unparalleled. Consequently, Ptolemy’s scientific works, particularly “Almagest,” have become exemplary works for countless scientists across generations.

Ptolemy authored numerous other notable works on various subjects such as astronomy, astrology, geography, optics, and music, which enjoyed widespread recognition during antiquity and the medieval period. Examples of his works include “Canopus Inscription,” “Hand Tables,” “Planetary Hypotheses,” “Phases,” “Analemma,” “Planispherium,” “Quaternary,” “Geography,” “Optics,” and “Harmonics,” among others.

“The Canopus Inscription.”

The “Canopus Inscription” encompasses the comprehensive set of astronomical parameters of Ptolemy’s system, inscribed on a stele dedicated to the God of Salvation. The study of the “Canopus Inscription” has revealed that it predates the renowned “Almagest” by a significant period.

“Stages of Immovable Celestial Bodies”

“Stages of immovable celestial bodies” is not an extensive scientific publication by Claudius Ptolemy, dedicated to forecasting weather conditions on our planet. It explores one of the earliest approaches to meteorology, which involves observing the dates of synodic phenomena of stars in the vast universe.

“Analemma.”

Another publication called “Analemma” presents the intricacies of astronomical practices in a user-friendly manner.

“Planispherium”.

“Planispherium”, a compact creation by Ptolemy, provides a practical demonstration of the stereographic projection theory.

“Quaternion” is the main manuscript on astrology written by Ptolemy, which is commonly known by its second Latin title “Quadripartitum”.

During Ptolemy’s time, astrology was widely believed in by the people. Ptolemy was a product of his era and viewed astrology as an essential complement to astronomy. Astrology, as always, predicts cataclysms and various events on Earth, taking into account the influence of the celestial bodies; on the other hand, astronomy provides information about the positions of the stars, which is necessary for making certain predictions. Ptolemy did not believe in destiny; he considered the influence of the celestial bodies as just one of the many factors that determine events on Earth.

The importance of Ptolemy’s writings

Ptolemy and his Contributions to Astronomy

Ptolemy’s contributions have played a pivotal role in the development of the field of astronomy. His contemporaries immediately recognized the significance of his work, particularly his groundbreaking book “Almagest.”

Ptolemy’s work served as a catalyst for advancements and revisions in the study of celestial bodies. However, it was this very work that inspired Copernicus to formulate his own doctrine, building upon Ptolemy’s foundations.

Enjoying the record? Spread the word to your buddies!

Presently, we have released a piece written by Ariadna Argyros, titled “The Ptolemaic Dynasty”. This family tree represents a fascinating blend of Hellenism and the ancient Egyptian civilization.

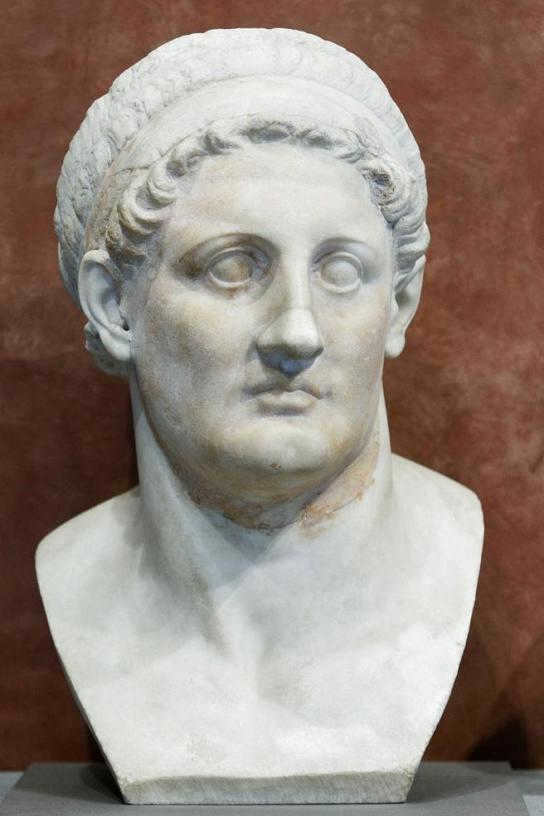

The Ptolemaic dynasty, established by Ptolemy I Soter, a military leader under Alexander the Great, governed Egypt for a span of three centuries, establishing a dominant and prosperous Hellenistic state. The Ptolemies abstained from military conflicts, promoted scientific advancements, and were venerated by the Egyptian people as divine beings.

In a matter of minutes, you can create your own Digital Time Capsule at no cost and begin compiling your family tree today. Additionally, within your Capsule, you have the opportunity to preserve for future generations a family chronicle, your personal life story recounted in first person, as well as photo and video archives.

The Reign of the Ptolemies in Ancient Egypt

In 332 BC, Alexander the Great successfully conquered the land of Egypt, which was then under the control of the Persians. This conquest took place during Alexander’s campaigns against the Achaemenid Empire. Following Alexander’s demise, his empire was divided among his loyal generals known as the Diadochi. Ptolemy, who not only served as one of Alexander’s trusted generals but was also his close friend, emerged as the ruler of Egypt and crowned himself as Pharaoh.

Ariadne Agiros

Ariadne Agiros is a professional in the fields of Egyptology and anthropology. She completed her Master’s degree in Egyptology at the University of Chicago in 2020 and holds a Bachelor’s degree in Anthropology from the University of Vermont. Ariadne’s primary area of expertise lies in the study of Ancient Egypt, particularly focusing on funerary rituals and culture. She is also well-versed in archaeology and museum work. Outside of her academic pursuits, Ariadne actively participates in archaeological excavations around the world. Additionally, she generously volunteers her time in museum education and outreach programs aimed at children. Ariadne finds joy in playing soccer, watching television, and spending quality time with her beloved bearded dog, Guy.

The rulers of the Ptolemaic dynasty cleverly adopted the title of Pharaoh and constructed numerous monuments featuring their own Egyptian-style depictions. This strategic move not only helped to establish their legitimacy but also garnered support from the native Egyptian population.

The Ptolemies, in numerous other manners, maintained Hellenistic customs, frequently to the detriment of the Egyptians. These monarchs enforced the dominance of the Greek language in their empire, all the while adeptly positioning themselves at the heart of Egyptian society and spiritual existence. Over the following centuries, Egypt, particularly its fresh capital Alexandria, emerged as the focal point of Hellenistic culture and evolved into the wealthiest and most formidable of Alexander’s successor states.

Following the death of Alexander in 323 BC, a power struggle emerged among his deputies. Perdiccas, acting as regent on behalf of Alexander’s half-brother Philip III of Macedon, appointed Ptolemy as the satrap of Egypt. As Alexander the Great’s empire crumbled, Ptolemy quickly established himself as an independent ruler, successfully defending Egypt against the encroachment of Perdiccas and other generals contending for control of Alexander’s domain. In 305 BC, Ptolemy emerged victorious and assumed the titles of king and pharaoh, adopting the name Ptolemy I Soter. Subsequently, all male successors followed suit by adopting the name Ptolemy, while women of the dynasty, including princesses and queens, favored the names Cleopatra, Arsinoe, or Berenice.

Ptolemy I had a deep respect for the religious and cultural traditions of the Egyptians, although the initial Ptolemies did not fully adopt them. However, under the rule of Ptolemy II, Egyptian rituals started to be actively embraced. For instance, in accordance with the myth of Osiris, marriages between royal siblings became common. Additionally, starting from Ptolemy II, members of the dynasty themselves began to actively participate in the religious life of Egypt, such as being involved in the construction and reconstruction of temples or engaging in priestly activities.

In the midst of the 3rd century BC, Egypt stood as the wealthiest and most dominant among the states that were conquered by Alexander. However, after approximately a century, conflicts within the kingdom and external invasions weakened it significantly, resulting in a growing dependence on the Roman Republic. Cleopatra VII, striving to revive Ptolemaic authority, embroiled Egypt in a fierce rivalry with Rome, ultimately leading to the nation’s demise. Subsequently, Egypt transformed into one of Rome’s most prosperous provinces, and Alexandria maintained its immense significance throughout the Middle Ages.

Governance and society

The governance and society in Egypt were shaped by the presence of Greeks, who, despite being a minority, held a privileged position. Their influence permeated the entire country, resulting in the establishment of an educated Greek-Egyptian class that existed separately from the native Egyptians.

Egyptian Greeks

In terms of government and society, power was exclusively reserved for Greek citizens. They were the only ones who could hold positions of authority and influence. Additionally, they received a traditional Greek education, married within their own community, and adhered to Greek laws. There were no concerted efforts to assimilate Greeks into Egyptian culture.

As time went on, certain Egyptians who acquired knowledge of the Greek language managed to progress in their professional lives. When examined closely, numerous individuals who identified as Greek were actually of Egyptian descent. As a consequence, a social class emerged that was both bilingual and multicultural. Nevertheless, the majority of Egyptians did not experience the same advantages, since Greeks predominantly held the positions of wealth, authority, and influence.

The Ptolemaic dynasty encountered various external challenges from the Seleucid Empire in the eastern region. Apart from the significant expenses associated with these conflicts, the Ptolemies had to press Egyptians into military service. This practice of forcing their own citizens to fight in wars that did not concern them, while also burdening them with higher taxes to finance these battles, understandably angered and frustrated the Egyptian population. Consequently, sporadic uprisings against the ruling powers occurred.

The reign of Ptolemy IV Philopator, who ruled from 221-205 BC, marked a significant period in Egyptian nationalist sentiment. During this time, Horwennefer, a self-proclaimed pharaoh, established his rule over one nom and governed for several years until his demise in 199 BC. Following his father’s passing, Ankhwennefer assumed power and continued his leadership until Ptolemy V Epiphanes subdued him around 186 BC. However, the discontent among Egyptians persisted, eventually leading to future uprisings against the Ptolemaic dynasty.

The Ptolemies and the Religion of Ancient Egypt

Despite introducing administrative and cultural changes, the Ptolemaic rulers respected and preserved the rich Egyptian culture and religious beliefs. In fact, they actively supported and maintained traditional Egyptian religious practices and architectural forms.

Preserving the Ancient Gods

In the early years of their reign, the Ptolemaic kings and officials designed temples that closely resembled the traditional Egyptian temples. As time went on, the Ptolemies even enhanced and adorned existing temples, resulting in many surviving temples in Egypt being considered Ptolemaic constructions. These temples, with the patronage of the Ptolemies, served as important centers of education and worship. The cults of Osiris, Isis, and Horus particularly flourished during this period, leading to the creation of numerous temple statues. Archaeologists have discovered evidence of animal mummy offerings, as well as the creation of reliefs and busts, all of which were part of the public celebration of festivals.

And fresh deities

As is customary when two different cultures collide, the Ptolemies introduced certain religious practices of their own to Egypt. Ptolemy I established a brand new deity known as Serapis, who was a fusion of Egyptian and Greek gods. This was an effort to merge elements of Greek and Egyptian religions in order to establish the Ptolemies as legitimate rulers. In pursuit of this objective, the Ptolemies also embraced the tradition of declaring themselves as divine beings.

The queens of the Ptolemaic dynasty were also highly regarded and received considerable attention. Queen and pharaoh Arsinoe II, who was married to Ptolemy II, was frequently depicted as the Greek goddess Aphrodite, but with the crown of Lower Egypt. Her portrayal was further enhanced with ram’s horns, ostrich feathers, and other traditional Egyptian symbols of royalty and divinity. Cleopatra VII, the final ruler of the Ptolemies, was often depicted as Isis, wearing a small throne or a solar disk adorned with two horns as a headdress.

The women of the Ptolemaic dynasty played active roles in the realm of religion, suggesting that they had access to education, as they were required to possess knowledge of music and texts. The upper-class women received the most comprehensive and well-rounded education. The only exceptions were artisan families, who taught their daughters skills such as painting, writing, science, and mathematics.

Kings and queens often had similar levels of power, and in some cases, their power was equal. The Ptolemaic dynasty brought back the ancient Egyptian tradition of marriages between siblings, and both kings and queens governed together.

Art and Culture

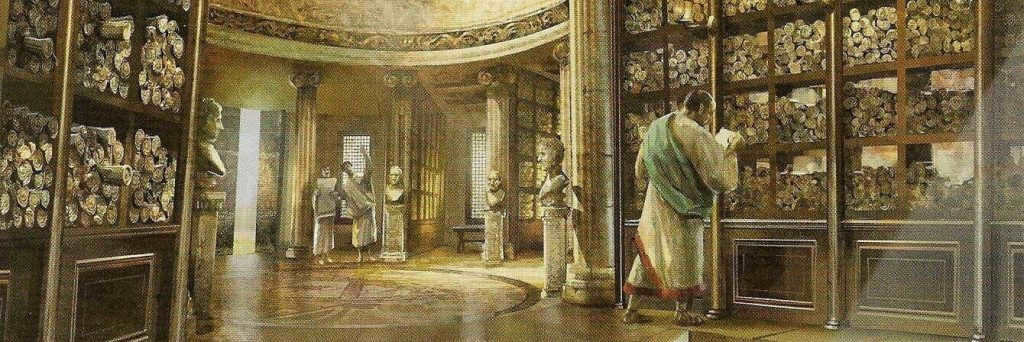

The Library of Alexandria, which was established by Ptolemy I between 300-290 BCE, was originally dedicated to the nine Muses, the renowned Greek goddesses associated with the arts and held in high regard in ancient Greek society. This institution became a prominent hub for academia, literature, and research, attracting the most accomplished Greek scholars from all corners of the Hellenistic world.

The Demise of the Library of Alexandria

There are multiple theories regarding the demise of this renowned library. These include:

- One theory suggests that a fire broke out when Julius Caesar burned the Egyptian fleet during the siege of Alexandria in 48 BC;

- Another theory proposes that the library was set ablaze by the powerful Caliph of Mecca in the 7th century AD;

- Some believe that the library was destroyed by Emperor Theodosius;

- There is also a theory that the library was demolished during the capture of Alexandria by Aurelian, amidst the revolt of Queen Zenobia of Palmyra in 269 AD.

Nevertheless, the true cause of the library’s disappearance remains an enigma.

The Combination of Egyptian and Greek Styles in Art

At first, the artistic styles of Greece and Egypt remained distinct from each other, but gradually they started to share more common characteristics. The preservation of the Egyptian art style reflected the Ptolemies’ desire to uphold Egyptian traditions in order to gain acceptance from the local Egyptians and maintain their rule.

One notable example of the fusion of Greek-Egyptian art can be seen in the portrayal of the Ptolemaic queen, Arsinoe II. Her depiction incorporates Egyptian iconography in her pose, the column supporting her, and the cornucopia she holds. However, her hairstyle and facial features clearly show a Greek influence.

In general, the artistic fusion depicted the women as more youthful, while presenting a balance of idealism and realism in the portrayal of men. The influence of Greek customs is evident in the emphasis on specific facial attributes. For instance, the artwork showcases Greek hairstyles, oval-shaped faces, rounded eyes, and petite mouths.

The decline and fall of the Ptolemaic dynasty

The end of the Ptolemaic era coincided with the rise of the Roman Republic. At this stage, the Ptolemies’ authority had significantly weakened due to external conflicts, as well as their constant plots to overthrow or assassinate one another. They were left with no choice but to form an alliance with the Romans.

About 150 years later, during the reign of Ptolemy XII, Rome had established a strong presence in Egypt. Its influence extended to Egyptian politics and possessions to the extent that the Roman Senate assumed guardianship over the Ptolemaic dynasty.

Following a series of failed attempts to overthrow the government, Ptolemy XII expressed his wish for Cleopatra VII to marry her sibling, Ptolemy XIII. In his last testament, he stipulated that they should rule together, with the Senate acting as the executor. This arrangement further solidified Rome’s control over the Ptolemies and, consequently, over Egypt as a whole. After Ptolemy XII’s demise, Cleopatra VII and Ptolemy XIII assumed the throne and entered into matrimony. However, Cleopatra’s authority was soon stripped away, forcing her to seek refuge in exile. It was during this period that she began devising her own rebellion, with the backing of none other than Julius Caesar himself.

Upon his arrival in Alexandria in 48 B.C., Julius Caesar was tasked with resolving a conflict in Egypt driven by nationalist sentiments. Given that Egypt was a crucial supplier of essential resources like grain to Rome, engaging in war with Egypt would have had severe consequences for Rome and its citizens. Cleopatra was discreetly brought to Caesar’s attention, and he agreed to support her claim to the throne.

In just a matter of minutes, you can register for your very own Digital Time Capsule for no charge and begin compiling your family tree today. Additionally, you have the opportunity to preserve your family’s chronicle, personal life story, photo collection, and video archives for future generations in your Capsule.

After being chased out of the palace by Ptolemy XIII and his advisors, Cleopatra was left with no choice but to seek refuge within the palace walls until Roman reinforcements could come to her aid. In a strategic move, Cleopatra decided to marry her younger brother, Ptolemy XIV, and was soon after bestowed with the title of pharaoh.

The marriage of Cleopatra and Caesar

She and Caesar had a romantic relationship and had a child named Caesarion. However, Caesar was killed in 44 BC. Subsequently, Rome was split between those who backed Mark Antony and those who supported Octavian. Cleopatra sided with Mark Antony and they eventually became romantically involved as well. In 32 B.C., they got married and had three children. Unfortunately, their marriage was not acknowledged in Rome because Mark Antony was already married to Octavia Minora, who happened to be Octavian’s sister. As you can probably guess, Octavian was not pleased with this!

Octavian’s Triumph

Rome has never been known for its equitable treatment of women. They were explicitly regarded as second-rate citizens. Consequently, when the Roman leaders accused Cleopatra of seducing Mark Antony to further the conquest of Rome, support for both individuals plummeted. Seizing the opportunity created by this change in public opinion, Octavian initiated a war against his adversaries and emerged victorious in 31 B.C. by defeating the combined forces of Mark Antony and Cleopatra at the Battle of Actium.

Octavian subsequently bided his time for a year before proclaiming Egypt as a Roman province. He then traveled to Alexandria to confront Antony and Cleopatra. Antony, realizing that he was destined for execution, chose to take his own life by falling onto his sword. In accordance with ancient classical traditions, suicide was not considered a moral transgression – this particular view only emerged with the advent of Christianity.

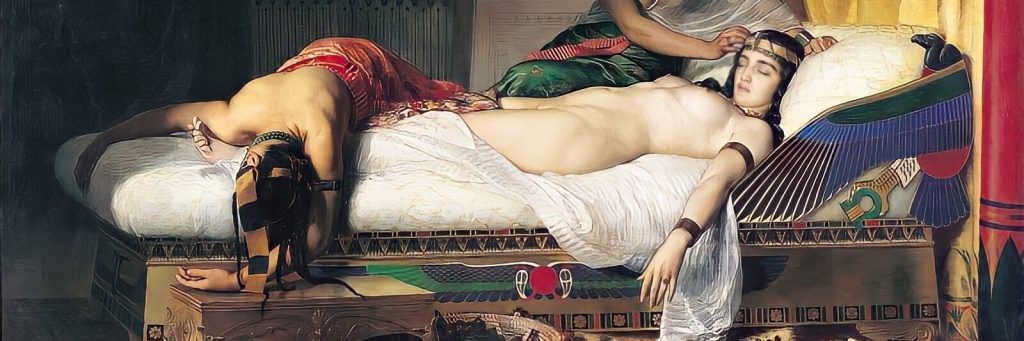

Cleopatra was aware that she would be brought to Rome to be publicly displayed as a symbol of Octavian’s triumph, which is why she also chose to end her life on August 12, 30 BC. The widely known tale states that Cleopatra perished after being bitten by a venomous asp, but there is no way to confirm or refute this account without additional evidence.

Following the demise of Cleopatra, Octavian gave the order for the execution of her teenage son and successor Caesarion. He was apprehended while attempting to flee and subsequently slain by Roman soldiers. With the deaths of Cleopatra and Caesarion, the Ptolemaic dynasty and Pharaonic Egypt came to an end. Although Alexandria remained the capital of the state, Egypt was assimilated into Rome, and Octavian assumed sole leadership of Rome, adopting the name Caesar Augustus. This marked the beginning of Rome’s transition into a monarchy – the Roman Empire.

Be the progenitor of your very own familial dynasty, safeguarding the saga of your family’s existence for future generations. Share your contact information to discover more.

PTOLEMY, CLAUDIUS (Latin: Claudius Ptolemaeus) (flourished 127-148), a renowned astronomer and geographer from ancient times, who finalized the geocentric system of the universe (commonly known as the Ptolemaic system) through his dedicated efforts. Little is known about Ptolemy’s origin, birthplace, and dates of birth and death. The years 127-148 are derived from Ptolemy’s observations conducted in Alexandria and its surrounding areas. His star catalog, which is a part of his astronomical work The Almagest, is dated to 137. Other information about Ptolemy’s life comes from later sources and is somewhat questionable. It is mentioned that he was still alive during the reign of Marcus Aurelius (161-180) and passed away at the age of 79. Thus, it can be inferred that he was born towards the end of the 1st century. Ptolemy’s most renowned works are Almagest and Geography, which became the pinnacle of ancient scientific achievements in the fields of astronomy and geography. Ptolemy’s works were considered so impeccable that they dominated the scientific community for 1400 years. During this time, Geography underwent minimal major revisions, and the contributions of Arab astronomers were mainly confined to minor refinements of The Almagest. Although Ptolemy was highly revered as an authority in ancient science, he cannot be described as a brilliant mathematician, astronomer, or geographer. His talent lay in his ability to gather the research findings of his predecessors, utilize them to enhance his own observations, and present them in a cohesive and comprehensive system that was presented in a clear and refined manner. The exceptional reference works he produced facilitated the maintenance of a relatively high level of knowledge in the respective subjects. It can be said that the modern era of scientific research in these fields began with the overthrow of the authority of The Almagest and Geography.

Almagest.

The name Almagest is derived from the Arabic definite article and the Greek word “megiste,” which translates to “greatest” (originally known as Matematikae Syuntaxis or Mathematical System). This monumental work signifies the culmination of centuries of research conducted by Greek astronomers in their quest to elucidate the intricate movements of celestial bodies. Comprising of 13 books, Almagest not only provides a comprehensive description but also offers an in-depth analysis of the astronomical knowledge prevalent during that era.

Books I and II of the Almagest provide an initial overview that explains Ptolemy’s fundamental astronomical assumptions and the mathematical techniques he employs. Ptolemy presents evidence supporting the Earth’s spherical shape and its central position within the universe. He assumes that the Earth remains stationary while the sky undergoes a daily rotation around the celestial axis. In Book I, Ptolemy includes a table of chords that corresponds to angles ranging from 1 /2 to 180 degrees, with increments of 12°. This table, which resembles a sine table for half angles, was inspired by a lost work by the Greek astronomer Hipparchus (c. 190 – after 126 BC) and served as a foundation for the further development of trigonometry. Book II explores various methods of mathematical geography, such as determining the longest day of the year for a specific latitude and calculating the latitudes (“climates”) within the inhabited regions of the Earth based on the longest day in those areas.

Books III and IV explore the movement of the Sun and Moon. Ptolemy embraces Hipparchus’s theory to explain the peculiarities of solar motion (which are actually caused by the ellipticity of the Earth’s orbit), utilizing the concept of epicycles and eccentrics. Ptolemy’s explanation for the Moon’s orbit is significantly more complex. He proposes that the Moon travels along an epicycle, with the center of the epicycle moving from west to east along an eccentric deferent. Simultaneously, the center of the deferent rotates around the Earth from east to west, and this entire mechanism lies within the plane of the Moon’s apparent movement. From the perspective of an observer on Earth, the opposing motions of the epicycle center and the deferent offset each other in relation to the line connecting the Earth and the Sun. As a result, the epicycle appears at the apogee of the excenter during the new and full moons, and at the perigee during the first and last quarters. This model effectively addresses the main limitation of Hipparchus’s theory regarding the Moon’s revolution and accounts for the periodic “wiggling” of the lunar apogee, known as ejection, for which Ptolemy nearly obtains the correct value.

In Book V, a range of topics are covered. These include the continuation of the development of the theory of the Moon’s orbit, the description of the construction of the astrolabe, the estimation of the sizes of solar, lunar, and terrestrial shadows, the measurement of the diameters of the Sun, Moon, and Earth, as well as the calculation of the distance to the Sun. Moving on to Book VI, the focus shifts to solar and lunar eclipses. In Books VII and VIII, the stars are described according to their constellations. Each star is assigned a latitude and longitude in degrees and minutes, and their magnitudes are measured on a scale ranging from 1 to 6. However, it is not entirely clear how much of this catalog was based on Ptolemy’s own observations and how much was borrowed from Hipparchus, considering the precession that has occurred over the past three centuries. The book also delves into topics such as the precession of the equinox point, the structure of the Milky Way, and the construction of the celestial globe.

Books IX-XIII are dedicated to the study of the planetary motion, which was a problem that Hipparchus did not address. In Book IX, the author examines the arrangement of the planets, their distances from the Earth, and their revolution periods. It is here that the author introduces the theory of Mercury’s revolution. Book X focuses on the movements of Venus and Mars, while Book XI delves into Jupiter and Saturn. In Book XII, the author discusses the stationary and retrograde motion of each planet, as well as the maximum elongations of Mercury and Venus. The fundamental model proposed by Ptolemy portrays Venus and the three outer planets as bodies that move from west to east on epicycles. These epicycles have centers that also move in the same direction on eccentric deferents. The center of an epicycle is assumed to have a constant angular velocity, not around the center of its deferent, but around a point that lies on a line connecting the Earth with the center of the deferent. This point is located at a distance twice the distance between the Earth and the center of the deferent. The epicycles and deferents are inclined at different angles to the ecliptic. The motion of Mercury follows an even more complex scheme.

For more information, refer to ASTRONOMY AND ASTROPHYSICS.

The Study of Earth’s Physical Features.

In the field of knowledge, Ptolemy’s Geography held the same significance as the Almagest in astronomy. It was widely believed to encompass a comprehensive understanding of the subject and was considered practically infallible. As a result, until the Renaissance, theoretical geography strictly adhered to its principles. However, as a scientific treatise, Geography falls short compared to the Almagest. While the Almagest may have its flaws in terms of astronomy, it remains intriguing from a mathematical perspective.

In Geography, advancements in theory coexist with notable omissions in their practical application. Ptolemy commences with a clear explanation of cartography methods, including the determination of astronomical latitude and longitude, as well as techniques for representing spherical surfaces on a plane. He then delves into the main body of his work, which revolves around the approximate calculations of navigators and explorers. Although Ptolemy presents his study in a mathematical framework and provides an impressive catalog of over 8,000 place names – cities, islands, mountains, river mouths, and more – it would be incorrect to view this work as a scientific investigation.

However, due to the satisfactory presentation of theoretical cartography aspects within this book, even by modern elementary textbook standards, it is evident that Ptolemy recognized that the accurate coordinates of places had not yet been determined during his time.

Additional projects.

Ptolemy’s expertise and his remarkable talent for expressing himself clearly and concisely were also apparent in his other writings, such as his works on optics and music. The treatise on optics has only survived in a Latin translation from Arabic, which itself was a translation from the original Greek text that has been lost. This treatise consisted of five books, although the first book and the end of the fifth book have been lost. The third and fourth books focus on the reflection of light. Ptolemy used measurements to demonstrate that the angle of incidence is equal to the angle of reflection. The fifth book explores the refraction of light. It describes experiments conducted on the refraction of light in water and glass at various angles of incidence and seeks to apply these findings to astronomy in order to estimate the degree of refraction of light passing through the Earth’s atmosphere from a star. Ptolemy’s treatise is the most comprehensive surviving work on mirrors and optics from ancient times.

Ptolemaic Harmonics is considered to be the most scholarly and well-composed treatise on the theory of musical harmonies among all the surviving Greek texts. It holds the second position in terms of significance among the ancient music treatises, right after Aristoxenus (from the second half of the 4th century BC). However, Ptolemy’s work has a more practical focus. One of Ptolemy’s other works is a four-book treatise on astrology called Apotelesmatics, commonly referred to as Tetrabiblos. This work held the same level of authority in the field of astrology as the Almagest did in its own domain.

THE IMPACT OF PTOLEMY’S THEORY

For almost 1400 years, Ptolemy’s works had a significant influence on the field of science. However, his impact extended far beyond the realm of science and had lasting effects on social, political, moral, and theological perspectives. Ptolemy’s theory, which proposed an Earth-centric model of the universe, was widely disseminated, particularly through medieval encyclopedias. This theory played a crucial role in the Middle Ages and Renaissance, as it allowed for the reconciliation of Christian doctrine with the wisdom of the ancient world. Scholars such as Albert the Great (c. 1193-1280) and Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) found value in Ptolemy’s teachings and integrated them into their own work, making them relevant and beneficial for centuries to come.

The exploration of the cosmos prompted a reevaluation of humanity’s connection with the surrounding world. The hierarchy of celestial bodies established by Ptolemy and his assumptions about their influence on specific groups of people were interpreted by the church as part of a grand chain of existence. At the pinnacle of this chain stood God and the angels, followed by humans, women, animals, plants, and finally minerals. This doctrine, combined with the Genesis account of the world’s creation in six days, served as the foundational backdrop for all European literature and prose from the Middle Ages to the 18th century. It was widely believed that this divine chain of being determined the social division of feudal society into three estates – the nobility, the clergy, and the commoners, each with their own distinct role in society. This perspective was so deeply ingrained in society that Galileo, who championed Copernicus’ heliocentric theory, faced trial by the Inquisition in Rome in 1616 and was compelled to renounce his views.